In venture capital terminology, a “unicorn” is a privately-held startup valued at over $1B – such companies are so rare as to be almost mythical. I’ve appropriated that term in politics to describe Democrats who win a major statewide office in deep-red states, or Republicans who win in deep-blue states.

Why do unicorns matter? Unicorns have to be centrists, capable of reaching across the aisle to get approval from the opposite party. So their very existence is both a sign of the health of our democracy, and an antidote to hyperpartisanship.

I did some analysis to see how unicorns have fared recently. For “major statewide office,” I limited the list to state governors or U.S. Senators. I excluded U.S. Representatives because there are plenty of blue districts in red states, and vice-versa; being elected as a Republican Representative somewhere in the state of New York isn’t too rare (in fact, there are currently six). I defined deep-red or deep-blue states are those won by Trump or Clinton by more than 10 points in 2016. There are 33 such states, meaning 99 officeholders (one governor and two senators per state) included in this analysis. Here are the states that qualify for unicorn status:

– Deep Blue (13): California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington

– Deep Red (20): Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, West Virginia, Wyoming

Note that Texas is not included as a deep-red state; Trump won by only 9.2% of the vote. So even if Beto O’Rourke had pulled off the upset against Ted Cruz, he wouldn’t have qualified as a unicorn.

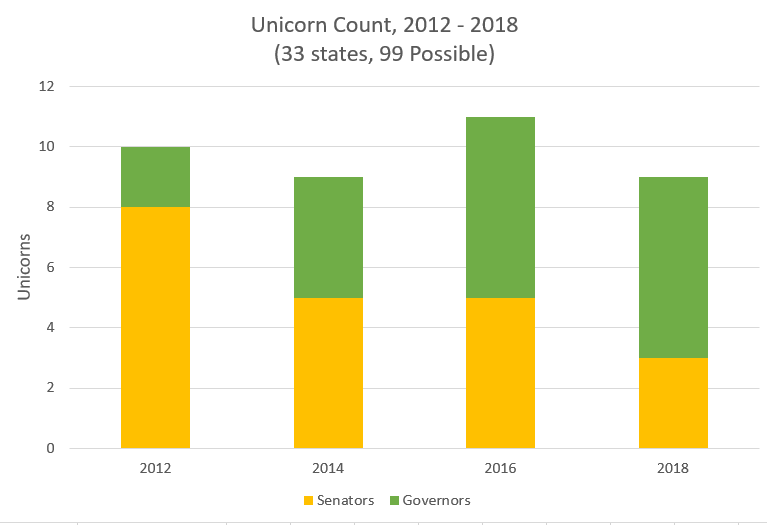

So, how many unicorns do we have? And how has that number changed since 2012? Let’s take a look:

At first glance, the change doesn’t look that significant, at least in the total number of unicorns, which has stayed consistently between 9 and 11 out of 99 possible positions. But take a closer look, and you can see that unicorn Senators are taking a beating; there were eight in 2012, but only three after the 2018 midterm election. In hindsight, maybe this drop should be expected as partisanship increases. Governors can focus more on state-specific issues and don’t have to vote with or against their party on hot-button national issues like Supreme Court nominations, building border walls, and the support or repeal of Obamacare. Senators don’t have that luxury; with the Senate so closely split, every defection from the party-line vote gets put under a microscope and risks angering the majority of the state’s electorate.

So let’s take a closer look at how unicorns did in the 2018 elections.

| Results of 2018 Elections in Deep Red/Blue States | ||

| Party | Governors | Senators |

|---|---|---|

| Democrats | John Bel Edwards (Louisiana) – no election Steve Bullock (Montana) – no election Laura Kelly (Kansas) – newly elected | Doug Jones (Alabama) – newly elected Joe Manchin (West Virginia) – retained seat Jon Tester (Montana) – retained seat |

| Republicans | Charlie Baker (Massachusetts) – retained seat Larry Hogan (Maryland) – retained seat Phil Scott (Vermont) – retained seat | None |

So, we gained two new unicorns (Doug Jones won in December 2017, but I’ve lumped him in with the 2018 elections, plus Laura Kelly), and lost four (Bruce Rauner, Joe Donnelly, Heidi Heitkamp, and Claire McCaskill). The three Republican governors (Charlie Baker, Larry Hogan, and Phil Scott), plus Senators Joe Manchin and Jon Tester successfully defended their seats. The Democratic governors Steve Bullock and John Bel Edwards were not up for election in 2018.

A few things I found surprising:

- I hadn’t realized there were three Republican governors in deep-blue states in the Northeast. And these weren’t one-time flukes – each has won twice, running as moderate Republicans.

- Montana, which went for Trump by over 20 percentage points, has two unicorns – its governor and one senator. Again, each has won multiple times as conservative Democrats in a deep-red state.

Looking ahead, three unicorns will be up for re-election in the next year or so – John Bel Edwards in Louisiana in November 2019; and Vermont’s Phil Scott and Alabama’s Doug Jones in 2020. In what’s shaping up to be another hyperpartisan election, how many of them will be left standing, and will there be any new blood to join them?

And as you might expect, these nine may not feel the need to stick with their party during the Trump impeachment process. All three of the Republican deep-blue state governors have publicly come out in support of the impeachment inquiry (although not in favor of impeachment yet). And the six deep-red state Democrats have for the most part taken a cautious approach. Steve Bullock (who is term-limited so does not face re-election) is in favor of impeachment. Jon Tester and Joe Manchin want to limit the inquiry to just Ukraine rather than bringing in the Mueller report or emoluments. Doug Jones criticized the phone call but declined to call Trump’s actions an impeachable offense. John Bel Edwards came out against the inquiry, saying it will accomplish nothing. Laura Kelly has not made a public statement.

Keep an eye on these nine as the impeachment process plays out. The six governors (three Republican, three Democrat) have no official role in the process, but are certainly facing pressure from their voters to break with their party, and several have already done so. The three Democratic senators will be in an interesting position if and when the process moves to the Senate for trial. Two of the three (Tester and Manchin) will not face an election until 2024, so they may not face immediate consequences if they vote to convict the president. Doug Jones is up for election in 2020 – will he vote to convict and risk alienating voters in deep-red Alabama?