by JAY WILDER – October 15, 2018

After the recent hearings and confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, a lot of people are discussing what a 5-4 conservative majority will mean for laws about abortion, healthcare, and campaign finance, among other issues. Although pundits frequently explain that the Court got this majority because conservatives have been more motivated than liberals to get the Supreme Court they wanted, that justification doesn’t tell the full story. It’s worth looking back at recent history and recognizing how big a factor luck and timing have been in shaping the Court. In the past thirty years, there have been three times where health issues led to unexpected openings on the Court; in all three cases, the timing worked against liberals. Let’s take a look.

First event: Justice Thurgood Marshall announces his retirement in June 1991, allowing George H.W. Bush to appoint his successor.

As an attorney, Marshall was known for arguing several civil rights cases before the Supreme Court, including Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down the “separate but equal” law for public schools. He was nominated to the Court by Lyndon Johnson in 1967 and was considered a reliably liberal vote. Marshall was determined to hand his replacement to a Democratic president, telling his clerks, “If I die, just prop me up!” But in June 1991, as his health was failing, then-President George H.W. Bush was riding high in the polls after the success of Operation Desert Storm, which made another four years of a Republican presidency increasingly likely.

At Marshall’s press conference announcing his retirement, he explained, “I’m getting old, and coming apart.”

Bush nominated the extremely conservative Clarence Thomas as his replacement, who was confirmed in October 1991, 12 days after a relatively unknown governor from Arkansas announced his candidacy for president. If Marshall’s health would have allowed him to stay on the court another year or two, there would be no Justice Thomas, but instead a liberal justice nominated by Bill Clinton.

Second event: Sandra Day O’Connor announces her retirement in July 2005, under George W. Bush.

On its surface, this seems like a reasonably timed decision – O’Connor was a lifelong Republican, appointed by Reagan in 1981. She and her husband made public and rather inappropriate comments at a 2000 election-night party bemoaning the apparent Al Gore victory; it would put off their planned retirement, as she did not want to hand her seat to a Democratic president to fill.

When the election results were put before the Court, she joined the 5-4 majority in Bush v Gore, ending the Florida recount and handing the 2000 election to George W. Bush. O’Connor was a moderate Republican, finding middle ground on several high-profile issues: abortion (Planned Parenthood v. Casey), affirmative action (Grutter v. Bollinger), and separation of church and state (Capitol Square Review v. Pinette).

O’Connor’s opinion about the Bush administration and the direction of the Republican Party soured considerably after the administration’s hard-right response to 9/11, including the “torture memos” that led to Abu Ghraib, and the treatment of the Guantanamo Bay detainees. She turned against the new Republican party, writing the majority opinion on Hamdi v Rumsfeld, in which she rejected the indefinite detentions in Guantanamo Bay and stated that U.S. citizens could not be detained without a hearing. During this time, Republican leaders like Tom Delay and John Cornyn spoke out against “activist judges” who were insufficiently conservative, leading to death threats against O’Connor and others. O’Connor refused to back down, fighting publicly for judicial independence, even when it meant calling out Republicans. Talk of her retirement under Bush seemed to have been put on hold. Unfortunately, her husband John suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, and by July 2005, his condition had deteriorated to the point where she felt she had to retire and move back home to Arizona to take care of him. Bush didn’t hesitate to nominate the extremely conservative Samuel Alito to take her place. If her husband’s health had held up for a few more years, O’Connor would have seen John McCain, a moderate Republican from her home state of Arizona, win the party’s nomination in March 2008. It’s not hard to imagine that she would have stayed on the Court in hopes of giving him the opportunity to nominate her successor, and likely have resigned at some point while Barack Obama was president, giving him the opportunity to fill her seat with a liberal, and keeping Alito off the bench.

Third event: Justice Antonin Scalia dies in February 2016; Obama nominates Merrick Garland in March.

After Scalia’s death, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senator Chuck Grassley (the head of the Judiciary Committee) wasted little time in declaring that no one nominated by Obama would receive a hearing; that the nomination should be made by whoever won the 2016 presidential election. Ted Cruz, who was on the Judiciary Committee, stated, “We have 80 years of precedent in not confirming Supreme Court justices in an election year,” (which is not entirely true). The Senate refused to hold a confirmation hearing until after the presidential election, leading to the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch under President Donald Trump in 2017.

It’s an admittedly morbid question, but I have to wonder if Republicans would have made a similar argument if Scalia had died, say, three months earlier, in October 2015. It’s possible, but they’d lose the reasonable-sounding “election year” sound bite, especially since there was the inconvenient precedent of Justice Anthony Kennedy being nominated by Reagan in November 1987, and confirmed in February 1988 during an election year.

So it’s reasonable that had Scalia died a few months earlier, Garland would have at least gotten a hearing. He would have had a difficult nomination fight in the Senate, where the Republicans held a slim majority, but it’s certainly possible that he would have been confirmed. He was respected on both sides of the aisle; in fact, some conservative commentators noted that Garland was the best justice they could hope for from Obama or Hillary Clinton, had she been elected. And if Garland had been confirmed, Neil Gorsuch would have been pushed back and been the nominee to replace Anthony Kennedy. And we’d have no Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

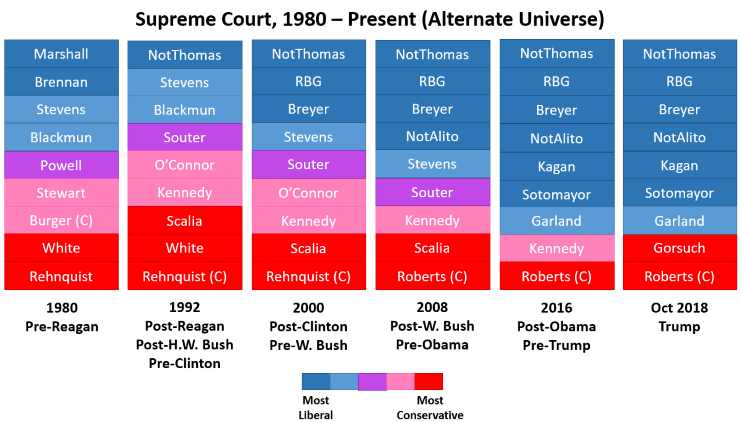

To give more context, I was looking for a way to show visually how the Supreme Court has evolved over the past 40 or so years, and came up with the following chart. It shows the ideological leanings of justices at key transitions in the history of the Court; the handoff from Democratic to Republican administrations and vice-versa.

This is obviously a simplification, as justices are never uniformly liberal or conservative across all issues, and everyone who’s ever sat on the bench would say that the Court focuses on the law, not politics. But examining the voting record shows that justices do tend to cluster together, so it’s worthwhile to evaluate these trends. Here are some insights:

The tradition of appointing moderates or centrists to the Court by either side has become more and more rare. The 1980 court was a picture of balance, with equal mixtures of liberals and conservatives, moderates and extremists, with the centrist Justice Powell as the fulcrum. Between 1980 and 1990, there were three moderates confirmed (Kennedy, Souter, and O’Connor), but none since then. The current Court is the first one without any real moderates; I would expect the number of 5-4 decisions, which is usually 15-20% of all cases, to set an all-time high.

For all the hype and hysteria about radical shifts to the left or the right, the Court has tended to stay remarkably balanced – only one time (between 1991 and 1993) was there more than five liberals or conservatives on the Court at the same time. And during that time, O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter frequently formed a group devoted to moderate decisions, to the frustration of their conservative brethren.

But in the spirit of “The Man in the High Castle,” let’s explore an alternate universe, one with a few minor changes to the events described above. Say Thurgood Marshall and John O’Connor’s health hold up for a few more years, and Scalia dies a few months earlier, and Merrick Garland is confirmed. Here’s the alternate history, shown graphically:

The Court looks much different – the most recent Trump nominee to replace Anthony Kennedy (Gorsuch in this case) becomes part of a lonely 7-2 minority instead of a 5-4 majority.

The point of this isn’t to encourage liberals to start constructing their dimension-traveling devices, but just as a reminder: Luck has a way of evening out in the long run.